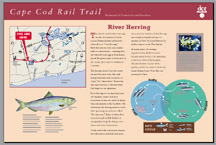

Herring Count 2009

Herring Count 2010

Herring Run Moratorium Will Remain In Effect Three More Years

by William F. GalvinHARWICH – The river herring harvest, possession and sale moratorium put in place three years ago by the state Division of Marine Fisheries will continue for another three years, selectmen agreed Monday night. Last October, the Massachusetts Marine Fisheries Advisory Committee approved the continuation of the moratorium based on the dearth of anadromous fish migrating up rivers in the state to spawning headwaters. Division of Marine Fisheries Director Paul J. Diodati has implemented the additional three-year ban as of Jan. 1, 2009, which includes those runs within municipalities which have been granted local control by the state. “We saw some initial positive signs of river herring population increases in spring 2008 as a result of these sacrifices,” Diodati said.

“We’ve seen fish every year but the last time we saw a significant number was in 1999,” Natural Resources Officer Thomas Leach said this week of the once prolific Herring River run. Leach said there has been improvement since the moratorium was put in place three years ago and last year there were a few days with significant numbers moving up the ladder at Johnson’s Flume in West Harwich. “Once again this is the state telling us they’re giving us permission for us to close the run,” Selectman Ed McManus. His reference was to efforts by the town to close the run four years ago, before the state instituted the first moratorium, because of depleted fish stocks. A year later the state mandated the closure.

There remains a lack of recovery in the river herring runs in the commonwealth, DMF officials said in a prepared statement announcing the extension of the moratorium. “All available information indicates that the number of spawning river herring entering the runs in the spring of 2008 remained well below average and mortality remained high,” officials stated in the DMF New letter. “But there is some good news. The moratorium appears to have helped stabilize the runs, although at lower levels, and many of our runs showed a slight 2008 increase in the number of spawning fish.”

DMF officials predict three more years of a moratorium will allow the maximum number of spawners to complete an entire life cycle, thus increasing the probability of stock recovery. The state fisheries agency admitted there are currently unidentified factors contributing to morality. It conducted a study on the impacts of river herring by-catchin the sea herring pelagic fisheries which found 70 percent of vessel trips yielded no river herring by-catch, and only a very small number of trips had significant quantities, with annual estimates between 285,000 to 1.7 million pounds. “While significant, this amount of mortality is not sufficient to cause the coastwide decline in river herring stocks and so there must be other, currently unidentified factors contributing to mortality,” the study concluded.

Leach said the Harwich Conservation Trust and the Cape Cod Commercial Hook Fishermen’s Association will conduct a comprehensive river herring counting program in the run this spring. They are looking for volunteers to do a herring count once the run begins. Leach estimated it would start in mid-April and continue through mid-June. He said 40 people have volunteers to assist with the count. “One of the goals is to estimate the number of fish in the run,” Leach said. “We don’t know what that number is.”

Leach said Ryan Mann, outreach and stewardship coordinator for HCT and Lara Slifka, cooperative research program coordinator with the CCCHFA, also a member of the conservation commission, will be overseeing the survey. Residents interested in volunteering to assist with the count can contact Mann at the trust’s office in South Harwich. Mann said the commitment can be as little as 10 minutes a week, but volunteers can do more.

HARWICH - (1/29/03) In 2003, The Board of Selectmen voted there would be no taking of herring from the town runs for the next three years. Selectmen Monday night (1/26/03) voted to put in place a moratorium to protect the dwindling resource. An initial concept for protection was floated by Tom Leach, Natural Resources Director, who recommended limits be reduced and a prohibition be put in place for the 2006 season to protect juvenile alewives and help regenerate the resource, an idea that was supported by the Division of Marine Fisheries. Leach said he did not think the board would be ready to act immediately on a moratorium. But Selectman Cyd Zeigler questioned the delay, pointing out if the town waits too long the run could be lost. He said there has been a degradation of the entire run over the past 15 years.

HARWICH - (1/29/03) In 2003, The Board of Selectmen voted there would be no taking of herring from the town runs for the next three years. Selectmen Monday night (1/26/03) voted to put in place a moratorium to protect the dwindling resource. An initial concept for protection was floated by Tom Leach, Natural Resources Director, who recommended limits be reduced and a prohibition be put in place for the 2006 season to protect juvenile alewives and help regenerate the resource, an idea that was supported by the Division of Marine Fisheries. Leach said he did not think the board would be ready to act immediately on a moratorium. But Selectman Cyd Zeigler questioned the delay, pointing out if the town waits too long the run could be lost. He said there has been a degradation of the entire run over the past 15 years.

Alewife and blueback herring are known collectively as river herring.

Alewife and blueback herring are known collectively as river herring.