Danger The Shoals are so numerous about this locality that descriptions would be useless

(Note from sailing chart 1859)

and their enumeration would only tend to confuse.

No stranger should attempt their navigation, except by Main Ship Channel, without a pilot.

Even with the most perfect chart it is extremely hazardous.

Fig 1. The last of four Handkerchief Shoal Lightships. LV98 on station from 1930-1951 was easily seen from atop the bluffs in Harwich Port. | |

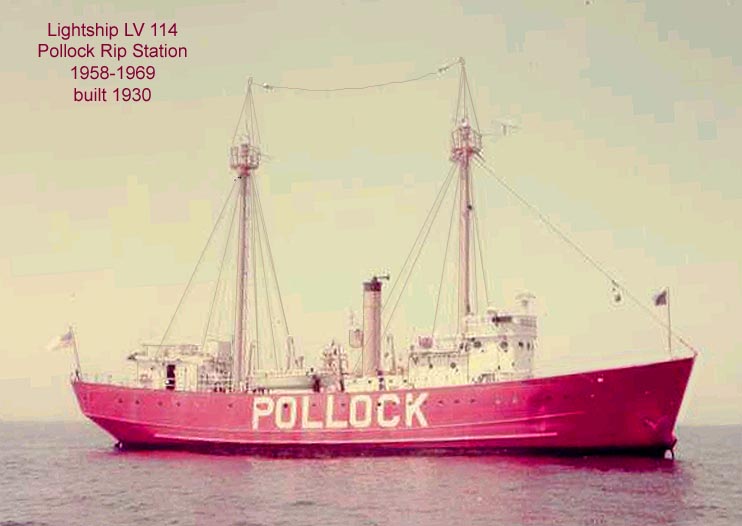

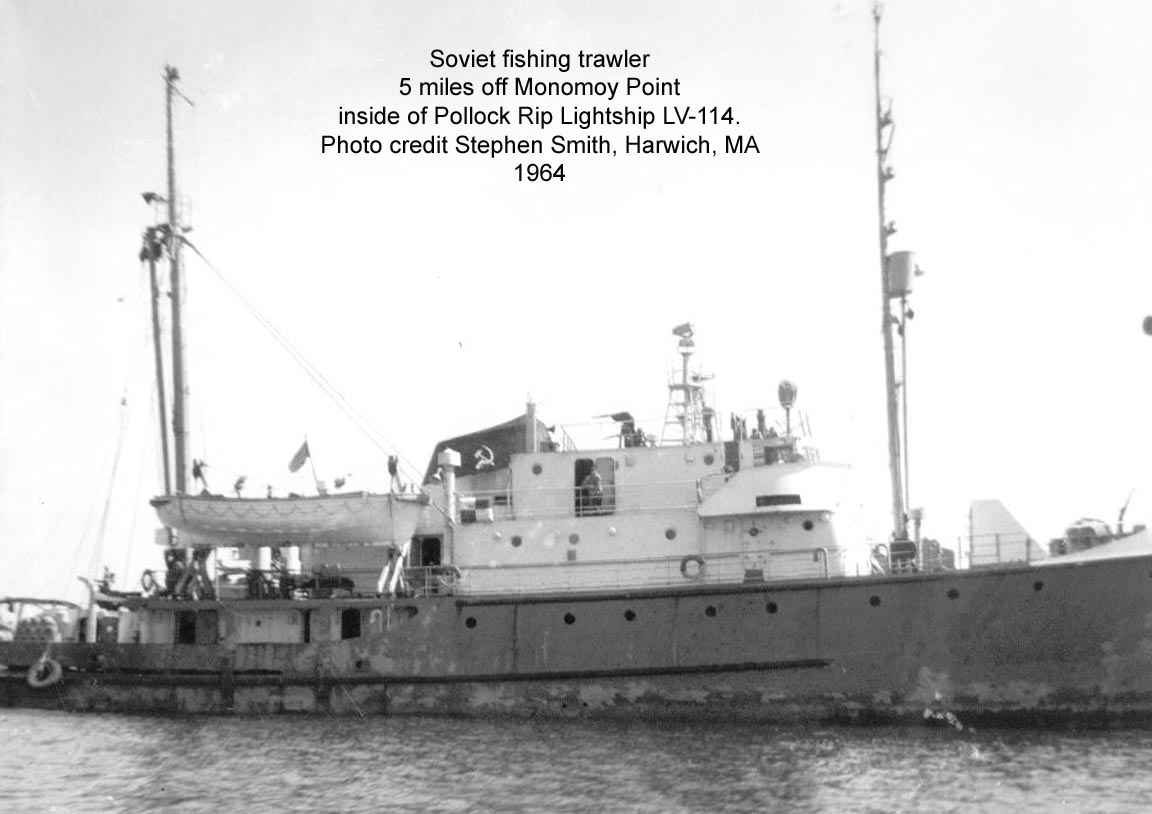

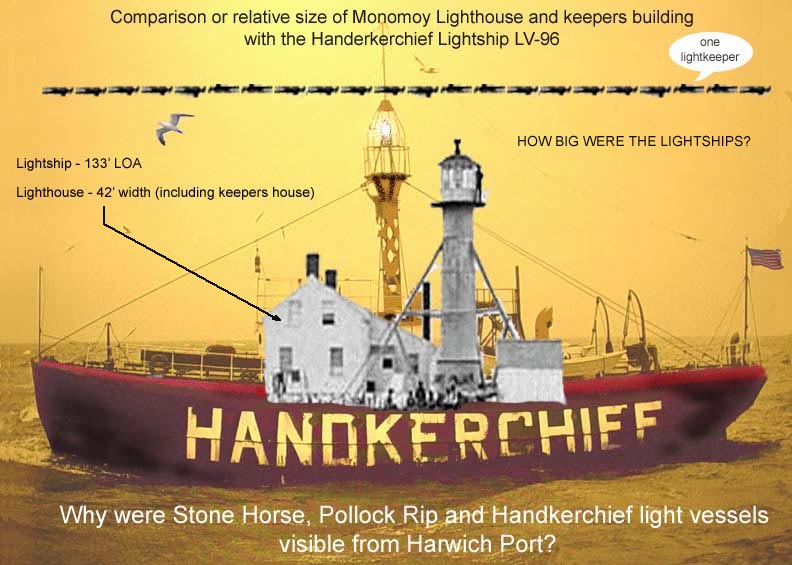

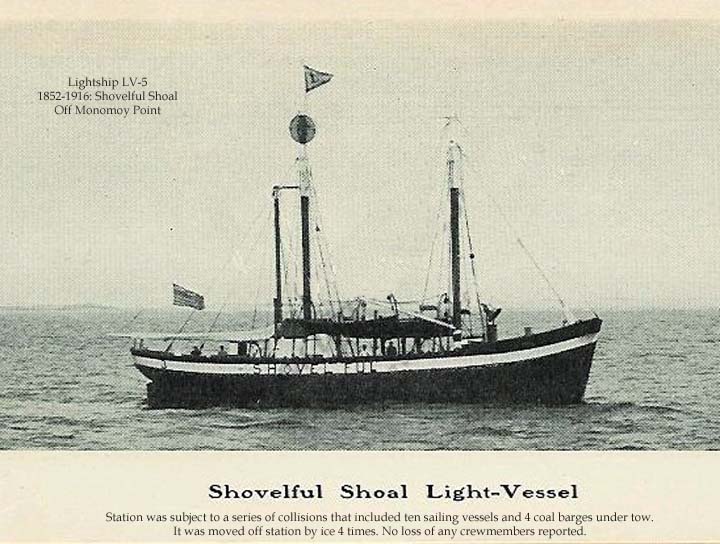

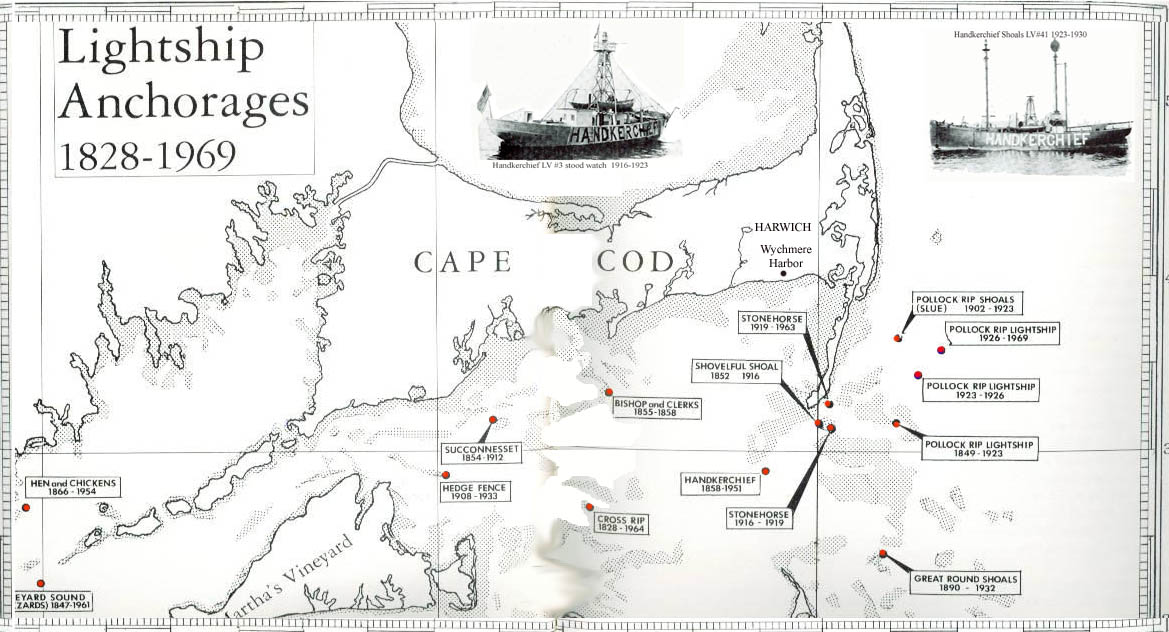

Like the crouch of a tree, Pollock Rip Channel and Great Round Shoals Channel converge in Nantucket Sound at Cross Rip. The only "safe" route for ships at sea between northern New England and New York, a need for an extraordinary number of light vessels emerged to mark a safe passage on through Vineyard Sound making this area known as "lightship alley". In fact, this channel had the most prolific number of lightships in the world. The "Monomoy Passage" route was heavily used by coastwise shipping to avoid an offshore passage seaward of Nantucket Shoals, but was subject to prolonged periods of heavy fog in the spring and summer months. As a result the elbow of the Cape became one of the most densely populated “graveyards” of the Atlantic. Up until World War II a vessel sailing down the Atlantic side of the Cape had to be navigated by sight and sound, looking for Chatham Light, listening for the whistle buoys on Chatham bar and the lightship at Pollock Rip at the entrance to the “slue”, a narrow and crooked channel where a slight deviation from course would bring a ship up hard and fast on the bottom. The areas uncommon ability to quickly produce dense fog from fair weather could reak havock, and when the fog lifted, observers could see a dozen vessels prudently “laying too” rather than risk trying to locate the “slue” by the sounds alone. For more then eighty years under the Lighthouse Service, the main lantern(s) of the vessels were kerosene lit, then later updated to brighter burning pressurized acetylene. The beacons of these vessels had a nominal range of about 12 miles under clear conditions1. Later with the advent of gas acetylene then safer generators the entire vessel could be electrified and the great lamps were replaced by 15,000 candlepower 1000 watt incandescent bulbs increasing the visble range of these vessels to 14 nautical miles at sealevel. In addition to the main light(s), the crew of the ship would set a riding light on the forestay, and later after electrification a permanent 360° lamp close by on the cross tree above the wheelhouse, as an anchor light serves today, when the vessel was laying properly in the night-time. This light was useful to help show the direction that the lightship was pointing or "heading" to indicate the direction of the current at the moment. This riding light was another clue that an approaching skipper could use to compensate his course so as to pass a lightship with sufficient clearance to avoid the possibility of collision by any cost. All too often, lightships were cleared by the tug only to be rammed or sideswiped by the barge or barges under tow. Hankerchief lightship No. 4 held a record being rammed a total of 15 times records state "she has suffered more from collision than any other lightship in the district" and all except three barges were commercial schooners. Coast Guard records state the "investigations concluded these accidents were "invariably" caused by vessels failing to allow for tidal current while attempting to cross the bow of the lightship".3 Considering that in 1884, LV-4 off Harwich Port logged 21,109 vessels passing her bow that year alone, 15 collisions in a 58 year career seems almost within reason. There are people here in Harwich Port, in their sixties and older, who recall, during easterly and southeasterly fog producing conditions, listening to the sonorous "mooing" of the powerful two-toned "diaphone" fogsignal of the Stone Horse lightship, easily the most prominent maritime sound along our shoreline until the last of these vessels was replaced by a buoy in 19632. Coast Guard records indicate that foghorn sound signals from lightships and powerful diaphones associated with lighthouses could be heard between two to 14 nautical miles under with variable conditions of weather and humidity. Under the right conditions the Handkerchief Shoal lightship, 10 miles south of Harwich Port, could be seen from Wyndemere Bluffs, it's large air diaphragm horn ( a 71" Leslie Typhon) occasionally could be heard as well. The 98's two story size made it a prominent feature on the horizon 4.5 miles SSW of Monomoy Point unitil June 7, 1951. It was replaced with a lighted whistle buoy which was later changed to an unlighted nun buoy #14. During the same time, Light Vessel (LV) Stone Horse (fig 6.) lay hidden by low lying Monomoy Island just seven miles from "The Port", but its diaphone sound (a 6" mushroom type air horn driven by two 40 HP kerosene engines) was routinely heard on foggy days from Herring River to Chatham until 1963. In Harwich Port under certain conditions the 7 mile distant Pollock Rip lightship (fig 2.) which used an air diaphone with 4-way multiple horns should have been heard over low lying Monomoy Beach. When the Snow Inn opened its doors in 1893, hotel guests found the distant fog signals from the lightships one of the oceans intriquing sounds among many attributes that would draw them back to Harwich Port year after year. One local Cape Codder, and retired Coast Guardman, Wayne Robinson recalls "I never heard the Handkerchief lightship, but Stonehorse, when it was southerly and fog was making was very plain here". "I often went out with the local fishermen, Charles V.Chase, John Barker, and others handling cod on shares. Coming back in the fog Stonehorse and her foghorn was the best way to find the Point and then around for home. I never heard Pollock Rip even fishing down the channel". Fog signals were sounds of safety, guiding sailing ships, tugs and steam vesssels at a time before the technological breakthroughs of long range electronic navigation (Loran) and radar. In 1989, Harbormaster Tom Leach proposed the idea for raising money for an electrified fog signal for the Wychmere Harbor breakwater. The idea to add this safety element to the existing aids to navigation in Harwich Port, much like the one's on the lightships, was quickly endorsed by then Coast Guard unit commanding officer Master Chief Jack Downey. When Snow Inn owner Richard Fennell was appoached for support, he was so enthiusiatic about the idea that he offered to foot the entire cost of the project. Afterall, fog signals in other coastal locations in New England create an interesting ambiance and were intermitant enough to be an attractive nuisance and Downey said he would "grease the wheels" with permitting. Two weeks later, the harbormaster received a call from Dr. Fennell advising him it was no go. He said he had discussed the plan with his hotel managers who insisted that the hotel guests were having enough problem with background noise from the channel, as clanking sailboat halyards and the diesel sound of fishing vessels departing in the wee hours, that it was not uncommon to have people from New York check-out. Another sound as a foghorn 500' from the guest rooms might just be the enough to empty the entire hotel. Had it been installed, it may well have saved the lives of two co-eds who were lost while kayaking in fog off Harwich Port in 2003. Somehow Kendall says Monomoy Island seemed lower at the time and the lightships could be seen over its bluffs. However, the simple test of standing anywhere along Wyndemere Bluff in Harwich Port, with an eye elevation of about 25' above sealevel, the lightkeepers house and abandoned light tower (47' above sealevel) at the Point are easily seen with the naked eye near the tip of Monomoy. Geographical Range of visibility tables allow for a range of viewing of 14.4 nautical miles from this height at low tide. Considering the relative size of the Hankerchief lightship was near three times the overall size and painted bright red and at an equivalent height above sealevel, it is very clear that all three lightships were easily within geographic range of visibility. In fact, the author recently viewed, through 7x35 power binoculars, Great Point lighthouse and the entire north shore of Nantucket Island, while standing on the bow of the Harbormaster boat, from about 1/2 mile off Harwich Port on a recent minus tide, leaving no doubt that Pollock Rip, Stone Horse, Hankerchief and perhaps Great Round Shoal, Cross Rip and Bishop & Clerks lightships would be visible from an advantageous location in Harwich Port in their day. The hardcover US Coast Pilot published in 1912 cost mariners 50 cents and lists the position and characteristic of light from each of the four lightships within sight of Harwich Port's bluffs at night. On a clear night, the non-occulting or fixed lights of each of the earlier lightships were reference objects. The Pollock Rip Shoals light vessel No. 73 lists a fixed white light on the foremast and a fixed red light on the mainmast with three kerosene oil lamps encirclng each mast; The Pollock Rip light vessel No. 47 lists a fixed white light on the foremast and a fixed white light on the mainmast with three kerosene oil lamps encirclng each mast; The Shovelful Shoals light vessel No. 3 lists a fixed red light on the mainmast; The Handkerchief light vessel No. 4 lists a single fixed white light on the mast. The same report lists Monomoy Point Light (fig. 3) as a fixed white light with a fixed red sector (between 255 and 267), height 47' above sealevel and a distance of visibility similar to a light vessel at 12 miles4. Like so many at the time, young Charles Kendall who kept an eye on "his" familiar lightships from the bluff, was shaken by details of the newspaper story of the 630 ton lightship being rammed by the 47,000 ton SS. OLYMPIC (sistership to TITANIC). OLYMPIC was in route from Liverpool to New York, in the shipping lanes near Nantucket Shoals in heavy fog. Ships inbound from Europe would get within range of the lightships by following shipping lanes, and then latching on to their radio homing signal and following it in. A lookout on the incoming vessel would then keep an eye peeled for the lightship and adjust the ship's course to avoid collision. Four men went down with the ship, 7 survivors being picked up by OLYMPIC. Three of the survivors died later of injuries and exposure. In 1936, in reparation for this disaster which made headlines world-wide, the British Goverment paid $300,956 for construction of a replacement lightship LV-112. At 149' it was the largest such vessel ever built. In 2004, the bell was recovered by divers from the wreckage of the LV-117. A report in March 1902 logged a staggering 500 vessels passing around Cape via the lightships within one 24-hour period. At that time it was estimated that 50,000 vessels passed the Pollock Rip lightship annually. Of course, all this traffic meant the area was target rich for collision or shipwreck. During the passage around Cape Cod more than 1,100 vessels were lost in Cape waters between the 'Backside' and Nantucket Sound exceed the number of vessels that came to grief at Cape Hatteras Diamond Shoals, known as the "Graveyard of the Atlantic". Fifty years later, half as many vessels passed this way (between September 1st and December 1952, 6,060 vessels were logged by lightship captains passing around the Cape). During the 18th, 19th and early 20th centurys, navigation by sextant was often less than a perfected art with respect to longitude where poorly trained navigators were far less reliable. Eastly passage of trade vessels, commercial schooners and later steamers from Europe to New England kept to a reliable safe lane at 42 degrees latitude. Vessels departing Europe for Boston would drop down to the latitude of Portugal and cross the Atlantic on a fixed east-west coordinate of 42°N with reference to Polaris. This had the advantage of a stop over in the Azores, for fresh food and water, sail below the negative current of the Gulf Stream and bring the vessels to the Atlantic coast in line with Cape Cod light, then New England's brightest and most reliable aid to navigation which was visible at more than 28 miles. At this point, captains would redirect their course to Boston. This stream of vessels added to the coastal traffic north-south where numbers once exceeded nearly 100,000 vessels annually passing the bended arm of the Cape at the "wrist". With all this shipping traffic we believed that we could find a representative photograph of a dozen ships passing the Cape in the Cummings collection, however, there is only one 1886 photograph in its fifteen volumes showing a six masted ship passing outside with two schooners off Nauset. Robinson offers some explanation for how important Chatham Bay and South Harwich were for these vessels heading north and south. If they had a headwind or bad weather they found the northeast corner of Nantucket Sound a suitable place to lay over for better weather. The area offered a lee in a northeaster and was out of the strong current further south. He recalls reading "it was recorded someplace that there were a hundred sail vessels "hold-up" in Nantucket Sound for many days. Imagine the amount of vessels there could be waiting to go east and north, at anchor between here and the (Monomoy) Point". With the advent of good weather these all might leave on the fair tide and a fair tide (and favorable wind) is what was needed to clear Monomoy Point. There is little doubt, the lightship captains could count on logging extraordinary numbers of vessels passing by at these times. The Atlantic Coastal Pilot in 1912 encouraged Chatham Roads (between Harwich Port and Stage Harbor) as a successful anchorage. It read "It is a good anchorage in 31/2 to 5 fathoms, with good holding ground, but is insecure for small craft in heavy southwesterly gales". Commercial schooners frequenting Pollock Rip Channel regularly would "lay too" or anchor in the protection of Chatham Bay as there were no safe harbors from Provincetown to Monomoy Point on the Cape's "Backside". Consequently, sailing ships and and Harwich Port were no strangers. Research done by the Sidney Brooks Scholars at the Brooks Museum, Harwich, Massachusetts published in 1998 proved there were 627 vessels owned and operated by Harwich sea captains between 1872- 1900. All of these vessels depended on the Sound lightship channel for passage in the northeast (the only alternative was to sail well outside the dangerous shoals of Nantucket island using the Great South Channel) and all these passed the Handkerchief shoal Light Vessel #4 (fig.9) close aboard at some point. The temptation to do business at Harwich or pay a visit home was often a factor in the stop over.Many of these vessels as large as 200 tons landed at the wharves in Harwich Port at Bank Street or a deeper spot close to shore at South Harwich off Red River at Deep Hole Wharf (off Old Wharf Road) where there was 9 feet of depth close to the beach to unload or await a change of wind or weather before departing again for New York, Providence, or Downeast. Figure 5. shows a section of the 1906 Eldredge Chart once owned by Capt. E. B. Snow. Some simple dead reckoning pencilings on the chart indicate his estimation of a doglegged course southwest from the anchorage just off of Red River entrance to clear Rogers Shoal and arrive at Handkerchief Lightship as 18 sailing miles. The Stone Horse LV#101 (fig.5) and Handkerchief LV#98 (fig.1) were served from an active Coast Guard station at Wychmere Harbor, shown on the right side of photo in figure 7. At the same period the Pollock Rip lightship LV#114 was served from USCG Station Chatham. There are a few fishermen and boaters left alive who remember sailing pass the Handkerchief lightship (located where N'14' is today). Leaving from Wychmere Harbor it was actually on a path of 203°M to Nantucket Harbor entrance while the Stone Horse was just around the corner off the tip of Monomoy. The Handkerchief Shoals Lightship was retired in 1951. Very early on, the Lighthouse Service Board decided it made sense to identify each lightship by hull color throughout Nantucket Sound. Pollock Rip was painted red; Handkerchief was straw colored; Shovelful was green; Cross Rip was straw colored with a red stripe; Succonnesset was red with white squares. Eventually the Lighthouse Board set the standard for all lightships to be painted red with white letters indicating the corresponding shoal. Young Tod would often coax his way onto the 26 foot service launch that went out to the ship for partial crew exchange on alternate weeks. Bill Lee had established the Lee Ship Building Company in 1932 on the site of what became the Harwich Port Boat Works (1938). He maintained an interest in the latter while, during the late 1930's, he founded the Red River Ice Plant. Located near the corner of Uncle Venies Road and Main Street (route 28) in South Harwich, Red River Ice Plant served almost 30 years the important needs for this product of much of the Cape. Refrigeration at home was still a novelty, at least on Cape Cod block ice for home use was mandatory, however, more than 200 families rented or shared lockers inside the ice plant where you kept your frozen foods until needed. Whatever needed to stay frozen fish or meat you could count on your locker at the ice plant. Of course, block ice was also important to the quality of life onboard the lightship as well. A monument at the Chatham Coast Guard Station (fig. 8) is dedicated in the memory of these lost souls and Capt. Elmer Mayo who saved 44 year old surfman Ellis. In a rare act, a bill rider authorized the US Lighthouse Department to build five homes in Harwich and one in Chatham. One for each widow and families of the six surfmen who lost their lives. One such home, that can be seen at 34 Oak Street Harwich Center, was built for the widow of Edgar C. Small and is referred to as the Monomoy Disaster House. The question that may be asked is how important were these lightships? Author Joseph C. Lincoln points out in his book Cape Cod Yesteryears (1935) the incredible numbers of vessels that continued to use the Lightship channel, regardless of the Cape Cod Canal. With "lightships at every shoal" "and in the vicinity of Monomoy, a savage tide to figure upon and to guard against" non auxiliary sailing vessels Pollock Rip Channel runs east west through Nantucket Sound. The 1912 'United States Coast Pilot - Atlantic Coast - Part III' lists a total of nine lightship positions guarding the channel, showing the way with sound and lights, through Nantucket and Vineyard Sounds. In 1912, the Pollock Rip to Newport channel lightship list (east to west) was as follows: Pollock Rip Shoals Light Vessel No.13; Pollock Rip Shoals Light Vessel No.47; Shovelful Shoal (later called Stone Horse) Light Vessel No.3; Handkerchief Light Vessel No.4; Cross Rip Light Vessel No.5; Succonesset Shoal Light Vessel No.6; Hedge Fence Light Vessel No.41; Sow and Pigs Light Vessel No.99; Hens and Chickens Light Vessel No.42; Brenton Reef Light Vessel No.39. In 1891, Gustav Kobbe wrote about his experience on a visit to the Nantucket Shoals lightship LV-1 for Century Magazine (the National Geographic of its day). The story Life on the South Shoal is a firsthand account of how lightships, unlike lighthouses which warned others of danger, were used by other vessels close aboard as a guide to the safe (deep) water. This is a graphic yarn that leaves us understanding the importance of lightships to the safety of shipping in an era of relatively primative navigational aids. Due to the frequency of vessels transiting the area, lightships for all the carnage they received saved countless lives. Wayne Robinson grew up on Bank Street in Harwich Port in the late 30's. While many of his friends were into hunting and fishing, he found he was spending most of his free time as a kid messin' around the shore and down at the harbor. Little did Robinson know his interest in Wychmere Harbor would become a lifetime affair. He joined the Sea Scout Ship which had a donated Crosby catboat at a mooring in Wychmere and in his teens worked part time at Harwich Port Boat Works. In those days parents thought less about risk and young Robinson frequently shipped aboard a converted trap boat owned by Capt. Charles V. Chase bound for the cod ground at Crab Ledge or the wreck off Monomoy Beach the WYOMING, a 6-masted schooner that went down at in about 7 fathoms near Pollock Rip lightship in March of 1924, and was now a "fishing reef". He quickly learned from Captain Chase how to use a compass, your wits and the lightships to find your way home. By 16, he had saved enough money to buy an aging friendship sloop named "IRENE B" which he and high school friends Roland "Rocky" Ryder, and John Buckley (both age 15) delivered home from South West harbor. Maybe we were niave then, but somehow it is hard to see parents allowing their kids to dare such an undertaking even with the communications and safety technology of today. By 1941, many of Robinson's friends were enlisting. Bill Lee by then had turned the boat yard over to Small to run the profitable ice plant. Also the recruiting officer at USCG Station Chatham, he convinced Robinson that a stint in the Coast Guard was what Uncle Sam needed. Eventually, he wound up serving at Monomoy Point Station, one of the last surfboat stations in New England located on the south side of the Powder Hole with three lightships nearly on its doorstep. By that time, radio was AM modulation (voice) no longer Morse key and they would hear the radio traffic between lightships and Chelsea Creek, Boston the repair and lightshiptender station for lightvessels at the time. One late afternoon, as Robinson recalls it was about dinnertime, Stonehorse Lightship broke radio silence as the Monomoy Point radio operator interecepted an important call "Monomoy Coast Guard, Monomoy Coast Guard.... This is US Coast Guard lightship Stone Horse shoal November-Mike-Golf-Alpha (call sign for LV#53) we are out of potatoes... please send supplies". After the War , Robinson took a job which became a career with Watson Small repairing boats at Harwich Port Boat Works. Robinson's words, in a note to the author, "the Handkerchief as I saw it (fig. 4) in the 1930's and 40's at this time was painted black. At one time, I remember seeing two heavy open work boats (probably x-navy hulls) on a mooring in the neihborhood of Jonesy's dock" (this would be the southeast corner of Wychmere harbor8), "One was painted red , and one was black, I believe these were used by the Coast Guard for making runs to the Stonehorse and Handkerchief lightvessels". During his service to the country in World War II, Lt. Bill Lee of Harwich Port was put in charge to tackle a hush—hush yet menacing problem that affected the Lightship Channel, which military powers wanted downplayed, especially at a time when the War was not going well. On December 12, 1941, one day after Germany declared war on the United States, the decision was made to send U-boats to raid American commerce. First blood was drawn on January 12th when the British passenger steamship, CYCLOPS, was sunk 300 miles off Cape Cod. In February, 432,000 tons of shipping went down in the Atlantic, 80 percent off the American coast. The following month, seventy ships were sunk along the coast. Things were so bad that M. Davis was a young girl during the War and remembers seeing a ship torpedoed in site of Harwich Port from the Snow Inn bluffs at Wychmere Harbor. In an attempt to avoid being discovered, US merchant ship captains hugged the coastlines, believing the U-boats would not try to close the inshore gap. This was not the case. In March, representatives of the petroleum industry met with Navy and War Department officers, warning them that if the rate of tanker sinkings were maintained, within nine months America's war-waging ability would be crippled due to lack of fuel oil. It was estimated that if this continued at its current rate we would lose 40 percent of our merchant ships and possibly the deaths of 3,000 seamen. The Germans proclaimed this period “Amerikanische Jagd-Jahrzeti” standing for “the American hunting season” as a cruel joke to identify this easily targeted theatre. The Coast Guard and Navy, in order to prevent a general panic, kept the public in the dark about the numbers of these sinkings off Massachusetts, yet on Cape Cod, innuendo about the frequency of the bodies of dead merchantmen washing ashore was growing. In February of 1942, while Stonehorse Lightship LV-53 was in transit to Chelsea Creek Lightship Depot at Boston for a much needed repair and overhaul it became caught in a gale off Race Point ( Cape Cod ). Blowing out to sea and having completely paid out her anchor chain with no bottom in sight her engine and radio also became disabled. If five days of this was not enough she had a sudden visit from a German U Boat who no doubt thought he was 'off course' so submerged and was not seen again. A patrol plane spotted Stonehorse and a cutter was employed to retrieve her. USCG Lt. Bill Lee was given charge of letting the contract to a commercial salvage company to remove the wreck and unplug the Canal. Unfortunately, this work was going painfully slow as they were unable to raise the vessel with cranes and barge. Lee became more and more frustrated with the contractor. As the work went on for 28 days, all shipping had to go through the Lightship channel and Pollock Rip or the Main Channel via Great Round Shoal out to the North Atlantic or were forced outside coming around the Cape from Boston to New York. Either way, they steamed right into the breech of the Wolf Pack waiting with their torpedoes off the backside of Cape Cod. For months, Cape Codders and Coast Guardsmen in charge of patrolling the outer beaches would frequently find bodies of merchantmen and oil washed ashore from vessels which were being torpedoed and sunk with amazing frequency. All this was often kept out of the press to keep the public from panic. In frustration over the contractor, and knowing our boys were dying, Lee asked to get a new contractor or be removed from the project. As a result, he was summarily dismissed from this duty and reassigned to Coast Guard Station Chatham. Later Lee learned that a solution was found. A large hole was blown with pumps and bucket crane below the ship which allowed it to settle in the hole. The Canal was reopened. To this day, there is a magnetic anomaly at that spot in the Cape Cod Canal presumably due to all the iron from that vessel in the bottom. By 1943, near the entrance to Cape Cod Canal, the mastheads of fourteen ships that had been the prey of the German "wolf-pack" were counted on approaching or leaving the canal. The Vineyard Sound Light vessel became an unintended tragety in 1944, unrelated to war, the LV-73 which had once served duty at this station for 20 years sank in the September 14th Hurricane. 19 years later, it was discovered by divers that hull plating where the storm anchor had hung at the bow, were stove in. Normally the 3 to 5 ton mushroom anchor is let go in intense weather. The crew unable to accomplish this, led to high seas slamming the anchor through the hull and sinking the ship. One story from LV#53 (fig.4) gives us a little insight to the life of the crew. Motor Machinist Mate Dave Murphy was aboard the Stone Horse Lightship in 1947 located just over a mile south of the tip of Monomoy. Dave and the crew would motor ashore to Harwich Port for supplies at Eldredge's Market, the mail plus the exchange of four crew from the Wychmere "station". He had probably met Tod Lee, a young lad who constantly hung around Wychmere Harbor busying himself in all that was interesting for a kid, at that time. Rounding the point at Monomoy they would DR a course to port. Fishing at the lightship consisted mainly of sand sharks so another type of fishing became popular. At night when the radio waves bounced off the ionosphere the crew would make contact with other Coast Guard Vessels around the world. The best catch was another Coast Guard vessel, an ice-breaker ship in the Antarctic. Murphy's lightship crew also found the service launch or the lightship's own 16 foot dory would make for some fine striper fishing on the other side of Monomoy during Spring, Summer and Fall. One December 22nd while returning to the ship with mail and Christmas groceries they met with a nor'easter and ended up riding a swell over the dunes right into the small pond ( Powderhole ) where they secured the boat and spent 5 days in the lookout station just staying warm and dry. They eventually enjoyed a belated Christmas dinner aboard the ship. The next vessel, Lightship LV-101 served at Stone Horse Shoal from 1951-1963 with almost an unblemished career, however, one tragedty is recorded. On May 18, 1955, while departing the vessel at Stonehorse shoal for reassignment, John D. Mortimer, Seaman Apprentice, USCG, Sligo, PA., was drowned when liberty launch was swamped by a wave. Cold winters, a frozen Sound often extended the lonely duty on some of these vessels which were often within sight of land. No one would argue that lightship duty was not arduous and without its hazards. There was always a chance of being rammed, parting chain, holed and sunk, or torn assunder by ice. It was among some of the least sought after dutys in the Lighthouse Service. Lightships were poorly lit and unsafe and crew morale was poor. There are even stories of crew abandoning the vessel7. Frequently, in order to insure dependable teams, crews were filled out by minorities mostly Portguese Americans who were good seamen and needed work in America. For lightships after transfer to the USCG in 1939, many operated initially with either an all-military or an all-civilian complement. This later gave way to a mix of military and civilian personnel. The mixed crews were in evidence well after World War II and a few of the Lighthouse Service civilian employees were still active into the 1970s. It really was not until well into World War II that conditions onboard the ships improved and the Coast Guard filled out the ships company with Coast Guard regulars who were assured one day of liberty for every two days of work onboard. The murderous four-month tour was eventually reduced to approximately 30 days10. Still things were not always easy for the Coast Guard to get men to accept this duty. Attorney Bill Hammett of Chatham recalled tales of a Coast Guard reservist friend who, if they failed to report to their monthly meeting, found their next assignment "enjoying" thirty days on the Pollock Rip lightship staring back at the Cape shore, wondering how your wife and kids were doing. Needless to say, lightvessel duty was considered by many in Coast Guard circles as more of a prison sentence to these assylums. "As you stare across the six miles separating you from the rest of the world, you sweep the shoreline with powerful 7x50 binoculars, hoping for a glimpse of bright colored cloth to remind you that there are girls out there somewhere. Some of your buddies, assigned to Ocean Station patrol duty, are out of sight of land for over a month at a time, but in a way they have it better. They can’t see land; they don’t have the option of visual references to the real world to tantalize their senses". "Your home, tethered by a huge mushroom anchor buried under tons of mud, snubs her bow now and then, jerking her downward as the bow rises. Even with the long scope of anchor chain, the effect is maddening"11. As a member of the Harwich town men's basketball team Craig recalls the team being invited to play Nantucket one very cold February in the early 60's, so the team boarded a DC-3 from Hyannis. Craig had a right-hand window seat as they flew over a frozen Nantucket Sound that afternoon they could see the Cross Rip Lightship LV-110 was partially buried under sheets of cracked and fractured ice that had apparently been pushed by the tide over the high bows of the vessel to height of the mast. One can only imagine the thoughts of the lightship crew of LV#110 at that moment, recalling the story of another lightship LV#6 (fig. 12) at the same positon being ripped from its mooring by ice and sunk at sea with the loss of all hands 42 years earlier. There is little doubt that the last decade of the 20th Century produced milder winters. Although certain corners of Nantucket Sound and Buzzards Bay continue to experience freezing today, the sub-zero freezing of the entire body of water is now very rare. There are stories from the colder part of the 19th Century of entire wood framed houses being dragged by horse team across Nantucket Sound to be set on a new foundation on the mainland or on the island. This heavy freezing of salt water ice represented special problems for the crews of the lightvessels that began in January of 1918 the Stonehorse, Handkerchief, Crossrip, and Hedgefence were bound solidly in a thick sheet of pack ice. This was at a time that Captain Richard E. B. Phillips of Dennisport had taken regular leave of the ship leaving another Dennisport native mate Henry F. Joy in charge of the Crossrip LV-6. There is an undocumented story that has come down through the years that Joy, having reach his furlough time climbed down onto the pack ice and walked to distant Nantucket Harbor where he reported to the CO at station Brant Point, who immediately ordered him back to the lightship. With the mid winter thaw on February 1st , 1918 the ice sheet began to move and the forces of ice and tide against the 63 year old LV-6 parted its riding gear. The powerless vessel was spotted on February 5th by the Great Point Light keeper east of the Great Round Shoal lightship station bound eastward with the moving ice. An all out search produced no sign of the vessel presumed sunk with all hands, all locals: Frank Johnson, Machinest, South Yarmouth, MA.William Rose, Cook, North Harwich, MA.Almon Wixon, Seaman, Dennisport, MA.Arthur C. Joy, Seaman, Dennisport, MA.E. H. Phillips, Seaman, West Dennis, MA.. 12 In 1987, a lightship bell presumed from LV-6 was recovered off Nauset Beach. The Phillips family is particularly noted in Harwich Port as large landholders at the time. An earlier lightship, one of four that served at the Handkerchief Shoals, Lightship LV-4 stood duty off Harwich Port a record 58 years (1858 - 1916) and used a 958 lbs hand operated bell as a fog signal. One can only imagine the endless monotony of each crew member on his four-hour anchor watch striking the ships bell for five seconds every minute in thick weather (considered rain, fog, snow, sleat)2. Stone Horse LV-101 is now a museum piece at Portsmith Naval Museum During the period 1820 -1983, 116 lightship stations were established by the United States at one time or another. This figure includes those stations that were renamed and moved to a different position to better serve the same purpose, and those taken over later by Canada. The number of stations existing at any one time peaked in 1909 when 56 lightships were maintained. By 1927, 68 stations had been discontinued, replaced by lighthouses or buoys, taken over by Canada, or considered unnecessary.In 1939, the mission of the Coast Guard was expanded to include responsibility for ATON, and resources of the former Lighthouse Service were transferred at that time. Lightship officers and crews, as well as other civilian employees, were offered two choices- integration into the Coast Guard with military rank commensurate with existing salary; or retention in civilian status under Coast Guard command. Exercise of these options resulted in about a 50-50 split. Of course, more often than not the lightship might part its heavy hauser chain leaving the mushroom anchor on bottom. In this case the ship carried a spare anchor usually at the ready on the starboard bow. When author Kobbe wrote his periodical story about life aboard a lightvessel in 1882, he reported that the sea bottom, 18 fathoms below the station, must be littered with "mushrooms" and chain. By that time the Nantucket Shoals Lightship had parted with its anchor 23 times since the stations inception in just 28 years, a loss average of nearly one anchor per year. The New Bedford scallop dragger CAPE ANN was driven ashore near Nauset Light in North Eastham in the early morning hours of March 6, 1948. The 84-foot vessel had just finnished an 11-day fishing trip on Georges Bank and had mistaken Nauset Light for the old Pollock Rip Lightship southeast of Chatham on the return home. Five crewmen were brought ashore by breeches buoy set up by the U.S.Coast Guard, while the captain and three others stayed aboard to help salvage its cargo of 700 gallons of scallops (scallopers today are only allowed 50 gallons or 400 lbs) plus much of the deck and fishing gear. By the late 1940's distant water vessels of many nations had found the rich fishing grounds of Georges Bank. Foreign factory ships were seen at a distance and often foreign trawlers were coming within the outer perimeter lightships at Pollock Rip, Great Round Shoal and Nantucket Shoals. In 1964, Stephen Smith of Harwich was a young lad and recalls a fishing trip with his dad, John, on a June day. They ventured with some other guests on this trip from Wychmere Harbor down Pollock Rip Channel when close aboard the Pollock Rip lightship they sighted an enormous Soviet fishing trawler with its prominent "hammer and sickle" emblem on the smoke stack, Steve was able to snap a remarkable photo (fig. 14) with his trusty Brownie Starflash camera. In 1871, the United States enacted legislation creating a 3 mile Federal line of protection off the shores of the United States. Until new legislation in 1966, foreign vessels could fish at risk of fine right up to the shore. The 1966 legislation redefined the territorial sea and contiguous zone at 12 nautical miles. In 1976 the US followed the lead of Canada with the Magnuson-Stevens Act creating the 200 mile territorial zone of protection ending the massive fishing effort by Great Britain, West Germany, Spain, Soviet union, and Portugal on Georges Bank. The use of lightships in Nantucket Sound came to an end in 1969 by the replacement of "Lightship Alley's" last vessel at Pollock Rip with a multi functional buoy. The lightship as a navigational aid in the United States came to a final end in 1983 when the last of the US lightships at the Nantucket Shoals, WLV-613, was retired. And so the great "congaline" of lightships through Nantucket Sound ended almost as easily as it began. It was spawned as many innovations are, from need. As technology improved and ran its course, the expense and risk of maintaining the lightships versus other more reliable forms of electronic aids made the cutback in the Coast Guard budget an easy decision. Today several lightships in the United States live on, not as navigational aids, but as floating museums dedicated to reminding us of the dangerous work that was once done by men to save an untold number of lives of other men. 2George Rockwood Jr. of Davis Lane, Harwich Port memory of these fog signals from the lightships is acute. Mr. Rockwood's local knowledge of lore on Wychmere harbor has made him an odds on expert of its history. 3THE SECRET is recalled by George Rockwood as a 60' ex-Coast Guard patrol boat that Bill Lee continued in a gray color scheme of the day. The boat was sold and painted white in 1948 to Carlton Francis Sr. a chemist who owned a home on the Herring River and renamed the vessel DENISON. The boat may have been a "6 bidder" type, a chase boats against bootlegging, and is remember for its powerful twin Fairbanks-Mores diesel engines. 4Short list of Commanding Officers of Hankerchief Shoals Lightship LV#4 (a 67 year career) History of Service of LV-4 5 6Tolls in the Cape Cod Canal in 1916 was as much as $16.00 for a trip by schooner, a considerable amount in those days. This, along with the narrow 100 foot width and shallow depth of the canal made many mariners continue to use the routes around the cape. As a result, tolls did not live up to expectations and the Cape Cod Canal became a losing proposition. Canal History, Cape Cod Canal US Army Corps of Engineers website 2006. 7Lightship service was affected by lack of funds. Lightships were poorly lit and unsafe . Anchors were lightweight and mooring chains weak. Ships were often absent from their stations and crew morle was lacking. The Lightships of Cape Cod Frederic L. Thompson, pub. 1983, page 26. 8Jones' dock refers to Howland Jones who owned a prominent house and dock on Wychmere Harbor off of Harbor Road two lots east along the shore from the Stone Horse Yacht Club docks. Jones, a Stevens Institute engineer owned a local commercial radio and TV station on Cape Cod and notably owned two famous yachts a motoryacht HAWKSBILL and a schooner SILVER HEELS. 9With the advent of radio direction finders and fog signals Vessels would often "home in" on lightvessels signal and turn at the last minute. The Nantucket Lightship at Nantucket Shoals was rammed many times by vessels trying to stay on course to New York from Europe. 10A History of U.S. Lightships by Willard Flint provides an excellent abstract of the history and development of the lightship in the united States and reasons for its demise. 11Light houses with wet basements. Charles W Lindenberg. A commentary on life aboard a lightvessel. 12Vessel designation: LV 6 (Cross Rip)at nightbeacon.com. . Various Lightships have served several missions including serving as departure marks by directing vessel traffic to the harbor fairway, and most often warning of the danger of treacherous shoals or the best water in areas such as Pollock Rip and other rips (shallow bars). In Nantucket Sound and Vineyard Sounds sandbars muddled traffic everywhere so lightships performed the job marking a safe path through fifty miles of this inside water route bewteen New York and Boston. The lightship assumed the place of a lighthouse where it became impractical to build such a rigid structure. All US lightvessels, beginning with No. 1 through No. 118, were given number designations under the control of the United States Lighthouse Service also known as the Bureau of Lighthouses.

Various Lightships have served several missions including serving as departure marks by directing vessel traffic to the harbor fairway, and most often warning of the danger of treacherous shoals or the best water in areas such as Pollock Rip and other rips (shallow bars). In Nantucket Sound and Vineyard Sounds sandbars muddled traffic everywhere so lightships performed the job marking a safe path through fifty miles of this inside water route bewteen New York and Boston. The lightship assumed the place of a lighthouse where it became impractical to build such a rigid structure. All US lightvessels, beginning with No. 1 through No. 118, were given number designations under the control of the United States Lighthouse Service also known as the Bureau of Lighthouses.

If we were to design a lightship what features would we want and in what order of importance? Now you ask yourself, this is not a trick question, what kind of work platform would be suitable? This process of trial and error began by lightship designers before the Revolution, however, were truly refined in the late 19th century. Lets start with a ridiculously stable hull between 110' and 150' in length with a high bow and ballasted keel, able to support heavy forces of anchor and chain against pounding overhead seas. Now to hold this boat on station we have advanced to, 1000' of nickel-steel anchor chain and two 4 ton class mushroom anchors. In order to take advantage of the forces on the hull, a watertight anchor hause pipe needs to be included on the centerline bow of the vessel just above the waterline. The advantages of being self propelled in the 20th century are obvious and an engine of sufficient horsepower can be used to "jog" the vessel while at anchor during a heavy storm to reduce force on the anchor chain.To see the ship, a strong light, preferably a fresnel lens and red painted hull to increase its visibility. For creature comforts and safety, an electric power plant (diesel generator) important for interior and night lighting and electronic equipment; compressor driven redundant automated fog signals; 2 life boats; Regular signals would include: a Masthead 1,000 watt light; Radio beacon; Submarine oscillator; Fog signals; Warning radio beacon. Emergency signals would include: Deck alarm; Below deck alarms; Hand operated bell.

Fig 2A. Development of lightships has gone from wood to steel during the 111 year period of the Cape Cod lightships.

Two lightship stations, each served by multiple vessels over a period of 111 years, in the Monomoy Passage had direct impact on Harwich Port over the years. Most notably, for Harwich Port, were the HANDKERCHIEF Shoal lightship and the STONEHORSE Shoal lightship marking two important locations in Pollock Rip Channel. Crew and supplies were transferred to these two lightships from a very small Coast Guard Station and berthing area that was maintained at the Snow Inn property on Wychmere Channel. The responsibility of getting men and supplies to POLLOCK RIP light vessel belonged with Chatham Coast Guard Station and a similar relationship existed between CROSS RIP light vessel and Brant Point Station. However, all these lightships were serviced and relieved by an alternate light vessel from the Lightship Annex at Woods Hole, later to become the US Coast Guard Base in 1939 or the USLHS lightship repair facility at Chelsea Creek, Boston.

Fig 2. Pollock Rip Lightship stationed 3.5 miles east of Monomoy Beach. Between 1849 and 1969 eight different light vessels served at this dangerous open water station.

Fig 4. The Stone Horse Lightship LV-53 (built 1893 West Bay City,MI) laid off the tip of Monomoy 17 years until 1951 when it was replaced by LV-101. Photo credit Watson Small.

In contrast, by 1968 it was reported that only an average of ten vessels per month passed by the Pollock Rip Lightship, pictured in figure 9. This fact shows the impact on coastal shipping other forms of transportation of freight and passengers as railroad, trucking and air travel were having. Further, improvements in navigation technology as radar and LORAN made navigation in fog reliable. Eventually, the need for expensive lightships in shipping lanes became obsolete. Lightship duty was not only tedious but fraught with hair-raising danger. Ships were frequently rammed and pulled off station by ice or storm. Several were sunk on station with the loss of most or all hands, but often crew members made the most of fair weather during their thirty day duty cycle finding things to clean, paint, and maintain on the vessel. The longevity of many of these vessels in a under funded service was often remarkable owing to repair and many vessels served more than 60 years.

Fig 5. Section of the 1906 George Eldridge chart 'Vineyard Sound to Lt. Ship Chatham' showing the northeast corner of Nantucket Sound and Pollock Rip channel Lightships

More research needs to be done to determine when the Wychmere Harbor auxilliary Coast Guard station began but it is believed to have been promoted by Bill Lee. The station was closed several years after the end of WWII. I read somewhere that the USLSS may have also kept a surfboat team at Harwich Port this would have been a valuable dispatch point for vessels in distress in Nantucket Sound. Nine valuable USLSS stations were strategically situated from Monomoy Point and ran the backside to Race Point.

Fig 8b. Surfman Seth Ellis and the Monomoy Life Saving Station crew pose for early postcard photographer in their surfbooat. Ellis was the sole survivor of rescue attempt near Shovelful Lightship.

Surfman Seth Ellis of Harwich Port, the father of Harwich Harbormaster (1958-1967) Joseph Ellis,is remembered as the sole survivor of the famous Monomoy station surfboat which was heavily manned by a crew of mostly Harwich lifesavers. Tragically, their lifeboat was overturned by waves during an attempted rescue of the crew of the schooner barge WADENA which was anchored grounded and inside of the Shovelful lightship in March 1902 (this position later renamed Stone Horse lightship beginning in 1916). This spot is immediately off the tip of Monomoy. According to John Hutchinson of Chatham who has carefully researched the story, the Wadena was not wrecked or sinking but anchored down by the towing tug against the current to await a favorable tide, not an unusual circumstance. With the change of wind and tide, the seas grew and an inexperienced crew aboard the barge raised a distress signal prompting the nearby Life Saving Station to launch a rescue effort.

Fig 8. Base of the Mack Monument obelisk at CG Station Chatham commemorating the rescue of surfman Seth Ellis of Harwich from a "watery grave". He died at a ripe old age (77).

The Channel once dog-legged between Monomoy Point and Pollock Rip was somewhat straightened through dredging around 1925. Even with the event of the opening of the Cape Cod Canal (1914) which rerouted a lot of traffic, ships sailing around Cape Cod inevitably passed through this area. It was not until after 1928, the federal government purchased the canal from August Belmont, and the US Army Corps of Engineers oversaw its widening allowing two-way traffic. The canal provides a 32-foot-deep channel north-south shortcut siphoning some 30,000 vessels each year from using "the lightship channel" to get around Cape Cod.

Fig 10. The Stone Horse Lightship built 1916 (Wilmington, Delaware) was a sentinel at Stone Horse Shoal for 12 years until it was retired in 1963. Photo credit Sidney Moody.

Fig 11. Lightship model LV-112 (Edwin Leidner, Eastham, Mass 1992)

At 3AM on June 28, 1942 and the S.S. STEPHEN R. JONES struck the north bank of the Cape Cod Canal 2,000 feet east of the Bourne Bridge and sank by the bow (many contend it was German espionage). This unfortunate accident and alledged act of war resulted in closing of the Canal to all military and commercial traffic. The American merchant vessels had been using the Canal shortcut as an inter-coastal supply route, as much as possible, to avoid being exposed to the intimidating German U-Boats which were plying waters east of Cape Cod. It was believed the Germans had sabotaged this vessel in order to close the Canal, thereby diverting shipping outside via the lightship channel.

Fig 12. The wreck of the S.S. STEPHEN R. JONES closed the Cape Cod Canal sending ships back throught the Lightship Channel and open water during WWII  Light Vessels (LV and WAL) - Record of Pre-WWII Shipbuilding

Light Vessels (LV and WAL) - Record of Pre-WWII Shipbuilding

Albert "Skip" Norgeot of Orleans, MA, spent years in the Marine Salvage and construction business and recalls grappling a 7,000 lbs lightship anchor during a salvage operation. It was at that time he learned that these unusually shaped mushroom anchors and their massive weight had a unique quality. Norgeot served a stint as Orleans Harbormaster believes, during very heavy gales when these ships were often pushed off station, if they were fortunate enough not to part chain, the round shape and coned shaft of their anchor would cause it to "walk" on the bottom. Thus the retreat of the lightship away from its station would be retarded or slowed by a zig-zag track in the sand as the anchor rolled or plowed a furrow through the sand and kinked up its chain, then unrolled itself in the opposite direction. The Pollock Rip lightship became known as "the Happy Wanderer" for the number of times it moved off station or broke free.

Fig 13. A lightship could drag its anchor in a slow zig-zag pattern during a gale. Maybe this is where the term "Anchor Walk" came from.

In later years, as regular shipping traffic dwindled life aboard the lightship was not completely filled with monotony. Still, the lightship channel was not without its share of marine mishaps and disasters. In this late period of reduced shipping, the Pollock Rip channel and Great Round Shoal channel continues to this day as the favored passage to the Georges Bank fishing grounds by the New Bedford, MA fleet.

Fig 14. Soviet fishing trawler photograph by Stephen Smith of Harwich at Pollock Rip. June 1964. Footnotes

1According to the United States Coast Pilot, Atlantic Coast, Part III, "From Cape Ann to Point Judith, Third edition published in 1912 by the Department of Commerce and Labor, Table of lighthouses and Lightships on Page 18 it is apparent the height of the mast of the vessel was the compensating factor in the range of the light, even in the case of the dimmer kerosene lamped vessels.

1858-?: ???

Fig 15. Overlay comparison of an average size lightship with the 47' Monomoy Light Tower an existing structure.

? - 1884: Stephen Howes, Keeper

1886-1890: A L Ellis, Asst Keeper

1890(1 mo. ): Charles E Ireland, Asst Keeper

1890-1893: A L Ellis, Keeper

1893-1902: A L Ellis, Master

1903-1904: Theodore B Brown, Mate

1906-1907: James B Frizzel, Mate

1907-?: Josiah P Hatch, Mate

?-1914: Ebenezer F Kelley, Mate

1914-1915: Walter D Chase, Mate

1915: Seth N Baker, Mate

1915: M F Rogers, Mate

1915-1918: William Kelley, Mate

1858, Oct 1, placed on Handkerchief Shoal (MA)-Passing vessels collided with this vessel in 1874 Sep 6; 1876 Aug & Oct 10; 1880; 1881; 1883 (2); 1885; 1887 Jul; 1890 Sep; 1899 Aug 15; 1899 Jun 6; 1902 Jan 27, Mar 18; 1903 Sep 15; 1907 Mar 12. Except for 3 instances of coal barges under tow, all involved sailing vessels. In 1885, records state "she has suffered more from collision than any other lightship in the district." Investigations concluded these accidents were "invariably" caused by vessels failing to allow for tidal current while attempting to cross the bow of the lightship.-

1874, Nov 17: parted chain, sailed to Hyannis awaiting replacement-

1875: Carried off station by moving ice, slipped chain and put to sea, off station 12 days-

1879, Jan 4: broke adrift in heavy gale, off station 18 days-

1884: Logged 21,109 vessels passing station during the year - 4 full rigged ships 212 barks, 281 brigs, 18,221 schooners, 148 s1oops and 2,247 steamers-

1898: Nov 27, dragged halfway to Cross Rip in gale back on station Dec 4-

1899: Feb 13, dragged 1 mile southwest of station, off station 2 days-

Monomoy Point Light, Massachusetts. Fishermen and sailors gathered at the seaside tavern, exchanging tall tales and quaffing a brew as they settled-in for an evening’s rest. Wreck Cove, though aptly named for its treacherous currents, drew mariners to its bountiful shores.The community of Whitewash Village thrived on the abundant marine life and foresaw the beginnings of a major settlement on the “elbow” of Cape Cod . What they didn’t know, was that Mother Nature hadn’t finished with the area yet.Officials established a light station at Monomoy Point in 1823 , preparing for a busy seaport. The sentinel, first lit in 1849 , cast its light from a Fourth order lens . The forty-foot tower was crafted from iron and lined with brick while the two-story Cape Cod-style Keepers Quarters was built of wood. The gleaming coastal light assisted vessels in navigating the perilous Pollock Rip for exactly one hundred years.But shifting sands began to fill-up the harbors and it didn’t take long for the shallow shoals to make passage impossible. The fishermen packed up their families and belongings and left in search of deeper waters. With the increase of power at the nearby Chatham Light, the beacon at Monomoy Point was deemed expendable and its lens was removed. The land was sold and used during World War II as a practice bombing range. Then in 1958 severe winter storms separated Monomoy Point from the mainland, creating an isolated island. Twenty years later , the relatively new barrier isle became two.The vast beaches, shifting dunes, freshwater ponds and salt and freshwater marshes became a protected habitat for wildlife, with an emphasis on migratory birds. Standing relatively alone in nature’s playground, Monomoy Lighthouse has survived the shifting sands and scourging currents that have all but erased the evidence of mankind’s ever being there.For all we know, Monomoy is not finished with its metamorphosis. The shoals may fill-in again, joining it to the Cape Cod mainland. There may be further dissections and the creation of additional islands. But one thing is for sure, the lighthouse on Monomoy Point has survived all of this, and with the protection of preservation groups, may continue to stand for generations to come.The Monomoy Light Station was restored in 1988 and is now used as an educational center by the Cape Cod Museum of Natural History.

Fig 16. Built to last, LV-5 spent 58 years one mile off Monomoy Point. She was struck ten times and moved off station by ice 4 times. No loss of crew reported in her career.

Fig 17. Chart showing location of he lightship anchorages of Nantucket Sound and Vineyard Sound over a total of 141 years of service.

Fig 18. Commercial impact of vessel landings. Two earlier more detailed maps of Harwich Port showing the busy commercial wharves along the shoreline of Nantucket Sound at Sea Street, Bank Street, Snow Inn Road, and Old Wharf Road (S.Harwich).

Webpage posted 01/25/06

Fig 19. The 1906 George Eldridge chart 'Vineyard Sound to Lt. Ship Chatham' graces the Harbormasters Office in Harwich Port. Tom Leach is dedicated to preserving the history of this rigorous service as it pertained to Harwich Port. See the Harbormaster's Cape Cod lightship slide presentation | |

Notes

Fig 20. Page 6 from the 1912 Atlantic Coast Pilot showed charts available to mariners. Note the lightship positions at Monomoy Point and Nantucket Shoal. | |

The station was originally named Tuckernuck Shoal from 1828-1852, then moved and renamed Cross Rip.

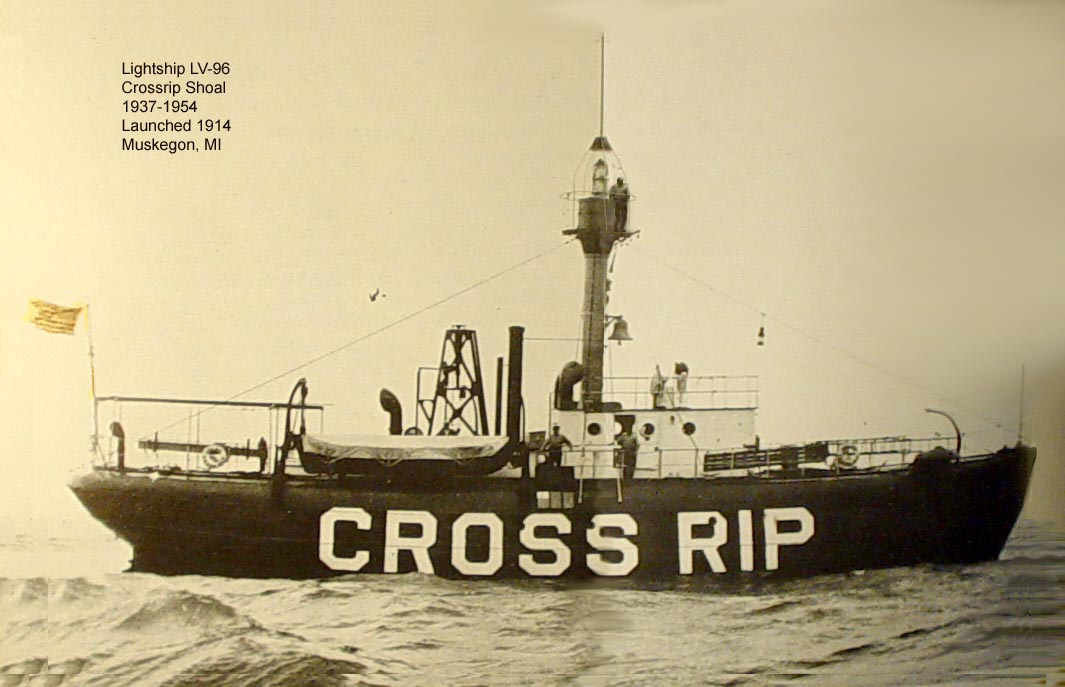

Fig 21. LV-96 served at Cross Rip Shoal for 17 years until it was replaced in 1953 by LV-110. One of the earliset lightship stations the history of a lightship at Cross rip begins in 1828. | |

Fig 22FF. LV-5 served Cross Rip long and hard beginning after the Civil War for 48 years. It was replaced by the ill-fated LV-6 which was swepted away by ice after only three years. | |

. . . . . . . . Keepers:Joseph C. Kelley first appointed on AUG 7, 1902 and left service in 1915.Robert E. Ellis appointed in 1915 and continued to serve. The sheer number of shipwrecks make it hard to positively identify the wreck, but Burke said he believes it might be connected to pieces of planking that have appeared on Newcomb Hollow Beach the last two winters. A similar piece of wreckage lies to the north of the Newcomb Hollow landing, and is about 26 feet long and 15 feet wide. It looks like the side of a large vessel. The ship's ribs, discovered this week, are approximately 500 yards south of the landing. At least 18 ships wrecked in the vicinity of the Cahoon Hollow Lifesaving Station between 1800 and 1927, according to National Seashore records provided by Burke. That area is close to Newcomb's Hollow.Historian Bill Quinn, who has written numerous books on Cape Cod maritime history and Cape shipwrecks, believes it could be the remains of the Logan, a 19th-century schooner refitted as a coal barge. The Logan went aground, Quinn said, around 1920 and was ultimately abandoned after it couldn't be towed off the sandbar."Unless you can find a quarterboard, they're very hard to identify," Quinn said yesterday by phone from Florida. The wood of vessels older than 100 years tends to go soft, he said. The hard oak planks of this latest shipwreck indicate the vessel may have wrecked less than a century ago.Old schooners were often converted to barges, Quinn said. They were towed in a line by a tugboat that would anchor the barge at sea when a storm threatened, then head for the nearest port.The barges still retained vestigial masts. After one barge blew from Nantucket to Bermuda in a storm, the crew rigged sails on the stumpy masts and sailed it back up to Massachusetts, Quinn said. The Life Saving Service, forerunner of the U. S. Coast Guard, was established in 1872 by the federal government. Eventually there were 13 Life Saving Stations strung out along the infamous “backside” of Cape Cod, from Woods Hole to Race Point in Provincetown. The Monomoy station had a crew of eight surfmen, who patrolled the outer beach on a regular schedule, looking out for ships in distress and, if necessary, ready to risk their own lives attempting a rescue. An article in the Boston Globe tells how Captain William Tuttle, of Harwich Port, and the crew of the Monomoy station, effected a daring rescue of five seamen from the schooner Ellen Morrison. The vessel, from Maine with a cargo of lumber, was caughtin a “furious gale” and driven on to Shovelful Shoal. She began to leak so fast that pumps were useless and she would not tack. The seas were breaking over the deck load when the jib stay snapped and the headsails were whipped to ribbons. Two miles away at Monomoy, Tuttle and his crew launched their lifeboat into the raging surf. Alter three hours of navigating through towering waves, the lifeboat came along side the schooner and, riding the crests of huge waves, and took off the sailors, one by one. The elbow of the Cape is one of the most densely populated “graveyards” of the Atlantic. In the late 1880’s a vessel sailing down the Atlantic side of the Cape had to be navigated by sight and sound, looking for Chatham Light, listening for the whistle buoys on Chatham bar and Pollock Rip and the bell buoy at the entrance to the “slue”, a narrow and crooked channel where a slight deviation from course would bring aship up hard and fast on the bottom. The area was well-known to sailors as a fog factory for its uncommon ability to quickly and unaccountably produce dense fog from fair weather. Often, when the fog lifted, observers on shore could see a dozen vessels prudently “laying by” rather than risk trying to locate the “slue” by the sounds of whistle and bell buoys alone. As testimony to the dangerous conditions off Chatham in the late 1880’s is the fact that during the first 12 years of Captain Tuttle’s command the Monomoy Station responded to 152 distressed vessels. A native of Harwich, Captain William Truman Tuttle lived on Sea Street in Harwich Port. He was captain of the Monomoy Station from 1882 to 1899. He died at age 50 from drinking contaminated water on Cuttyhunk Island. The accident occurred on the same day as a dramatic rescue of 22 men from a stricken freighter Aggersund 600 miles off Cape Race, Newfoundland, by the crew of the steamer Blankahelm.

"The unfortunate schooner was the five msted 28 year-old George W. Elzey Jr., which was in collision with coast guard cutter Acushnet off Cross Rip lightship last night as the cutter was proceeding to sea and the schooner returned to port," according to an Associated Press account. "No lives were lost in either mishap, and as far as could be learned, no injuries were suffered."

The Elzey sank within 20 minutes of the crash, according to Coast Guard reports, and its four fishermen were rescued by the Acushnet. The cutter remained on the scene to warn other vessels of the sunken schooner by flashing her searchlights, with the stern of the Elzey "slightly above" water.

The Acushnet was unable to pull the Elzey out of the shipping lane and the patrol boats Harriet Lane and Jackson were called to assist. The Elzey suffered another mishap in July 1916 when it caught fire while tied to an amunition pier in New York Harbor. The vessel was towed from harms way and the fire extinguished by a NYC fireboat crew.

Few people alive today can remember a time before a canal separated Cape Cod from "off Cape," a nomenclature including both Plymouth and China.

But when the first shovelfuls of Bournedale soil were dug to make the Cape Cod Canal 100 years ago this summer, many people thought it was a minor miracle.

Even before the Massachusetts Bay Colony was founded, area residents had agreed that a canal connecting Buzzards Bay and Cape Cod Bay was an excellent idea. Too many lives and trade goods were being lost in the shipping channels that swung around the Cape over treacherous shoals, earning the area the nickname "the graveyard of the Atlantic."

The problem was nobody could figure out how to make the canal idea a reality, despite endless studies and the grant of special state charters.

The sheer number of delays and false starts involved in creating the Cape Cod Canal made the Big Dig look like a cakewalk, said J. North "Jack" Conway of Assonet, who wrote, "The Cape Cod Canal: Breaking Through the Bared and Bended Arm."

"It constantly was before the Legislature and it constantly got shot down," Conway said. "Everybody wanted it, but nobody could agree upon how it should be done and who should do it."

The businessman who finally bankrolled a successful project was from off Cape and from out of state — financier August Belmont Jr., one-time owner of racehorse champion Man o' War.

"I hate to say it, but it took a New York yankee to build a Cape Cod Canal," Conway said.

Belmont wasn't the first famous name connected with the Cape Cod Canal.

Belmont's stake Calling the Scusset a river was a bit of a stretch. It was more like a salt marsh, said Cape Cod Canal Park Ranger Samantha Gray. She said the water "pretty much fizzled out" where the Sagamore Bridge is now.

Still, only a few of the eight miles defining the isthmus or shoulder of the Cape weren't at all navigable, Farson wrote. In 1697, the Massachusetts General Court passed a resolution ordering three men from the Cape to do a canal feasibility study, but nothing ever came of it, setting a pattern for the next 200 years.

There were surveys and plans but no action, Farson wrote, unless one counts the "Neapolitan Revolt" of 1880, when Italian workers hired to start work on the canal walked off the job after being denied pay, food and water.

When their employer, the Cape Cod Ship Canal Company, went belly up, the state Legislature paid the laborers' fare back to Boston and New York, Conway said.

But Belmont, whose Perry grandparents were from the Cape, was a more effective figure, Conway said. "He would be somebody like a Donald Trump today. He'd look at something and say, 'I'm going to do that.'"

The man who started New York's first subway invested about $9 million of his own money, Conway said. "Once Belmont got involved, there was no turning back."

Belmont was brought on board by Dewitt Clinton Flanagan, one of a group of investors who started the Boston, New York and Cape Cod Canal Company. William Barclay Parsons, who had worked on the Panama Canal, was chief engineer.

Work on the canal officially began on June 19, 1909, when crews on a two-masted schooner dropped a block of Maine granite into the waters off Scusset Beach, putting in place the first piece of the East End Breakwater along the north side of the canal, says the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which is in charge of the canal.

Three days later, Belmont scooped out a ceremonial shovel of dirt at the Perry Farm in Bournedale. The first dredge didn't arrive until much later in the summer, and 100-ton boulders left by the glacier whose departure had created the arm of Cape Cod had to be blown to bits with dynamite, but the canal was completed in five years.

Opening to great ceremony on July 29, 1914, it was 100 feet wide, 15 feet deep and crossed by three low drawbridges, one of them a railroad bridge, Conway said. This first version of the canal had a curve or elbow that was later removed.

"The canal that Belmont dug is not the canal we see today," Conway said. The modern canal "is a product of the Army Corps of Engineers who straightened the canal you had to zigzag through."

It turned out Belmont's toll canal was not the great commercial hope the financier and other investors had hoped.

The two currents from the different bays confused old-timers who were used to navigating waters off Cape. They were leery about approaching the openings to the drawbridges, which some ships jammed against in the swirling waters.

Cross culture In the spring of 1928, the Cape Cod Canal was officially sold to the U.S. government, which had expressed an interest for security reasons ever since a German U-boat sank a string of barges off Orleans during World War I. Federal officials made straightening the canal and widening it to 500 feet a WPA project that employed hundreds of people during the Depression.

They also replaced the drawbridges with the elevated highways of the Sagamore and Bourne bridges and built a railroad bridge with a vertical tower that lowers the rail bridge to sea level when trains need to pass.

But the changes brought by the canal didn't just affect the geography of the Cape — they solidified the sense of Cape Codders as a people apart.

Where they had once been residents of a peninsula and could theoretically walk off any time, now they were on an island. People started joking about old timers who never crossed the bridges.

"Absolutely that is the demarcation point for where the Cape begins," Conway said.

For tourists, crossing the canal in an eastbound direction is a signal that it's time to relax, even if they are stuck in traffic. "Once I cross the bridge, I'm on island time," says Jan Farrand of Southbridge, who is visiting Sandwich this weekend.

BELOW IS A REPRINTED STORY THAT IS A MUST READ

Life on the South

Shoal Lightship BY GUSTAV KOBBE from Century Magazine, August, 1891 No. 1. Nantucket, New South Shoal, pitches and plunges, tears

and rolls, year in and year out, twenty-four miles off Sankaty

Head, Nantucket Island, with the broad ocean to the eastward, and rips and

breakers to the westward, northward, and southward. No. 1, Nantucket, New South

Shoal, is a lightship — the most desolate and dangerous station in the United

States lighthouse establishment, Upon this tossing island, out of sight of

land, exposed to the fury of every tempest, and without a message from home

during all the stormy months of winter, and sometimes even longer, ten men,

braving the perils of wind and wave, and the worst terrors of isolation, trim

the lamps whose light warns thousands of vessels from certain destruction, and

hold themselves ready to save life when the warning is vain. When vessels have

been driven helplessly upon the shoals over which the South Shoal Lightship

stands guard, her crew have not hesitated to lower their boat in seas which

threatened every moment to stave or to engulf it, and to pull, often in the teeth

of a furious gale, to the rescue of the shipwrecked, not only saving their

lives but afterward sharing with them, often to their own great discomfort,

such cheer as the lightship affords. Yet who ever heard of a medal being

awarded to the life-savers of No. 1, Nantucket, New South Shoal? Before we left Nantucket for

the lightship I gleaned from casual remarks made by grizzled old salts who had heard of our proposed expedition that I

might expect something different from a cruise under summer skies. The

captain’s watch of five men happened to be ashore on leave, and when I called

on the captain and told him I had chartered a tug to take Mr. Taber and myself Out to the

lightship and to call for me a week later, he said, with a pleasant smile,

“You’ve arranged to be called for in seven days, but you can congratulate

yourself if you get off in seven weeks.” As he gave me his flipper at the door

he made this parting remark: “When you set foot on Nantucket again, after

you’ve been to the lightship, you will be pleased.” Another old whaling

captain told me that the loneliest thing he had ever seen at sea was a polar

bear floating on a piece of ice in the Arctic Ocean; the next loneliest object

to that had been the South Shoal Lightship. But the most cheering comment on

the expedition was made by an ex-captain of the Cross Rip Lightship, which is

anchored in Nantucket Sound in full sight of land, and is not nearly so exposed

or desolate a station as the South Shoal. He said very deliberately and

solemnly, “If it weren’t for the disgrace it would bring on my family I’d

rather go to State’s prison.” I was also told of times when the South Shoal

Lightship so pitched and rolled that even an old whale-man who had served on

her seventeen years, and had before that made numerous whaling voyages, felt

“squeamish,” which is the sailor fashion of intimating that even the saltiest

old salt is apt to experience symptoms of mal de mer

aboard a lightship. Life on a lightship therefore presented itself to us as

a term of solitary confinement combined with the horrors of sea-sickness. The South Shoal Lightship

being so far out at sea, and so dangerous of approach, owing to the shoals and

rips which extend all the way out to her from Nantucket, and which would be

fatal barriers to large vessels, the trip can be made only in good weather.

That is the reason the crew are cut off so long in winter from communication

with the land. The lighthouse tender does not venture out to the vessel at all

from December to May, only occasionally utilizing a fair day and a smooth sea

to put out far enough just to sight the lightship and to report her as safe at

her Station. The tender is a little, black side-wheel craft called the Verbena,

and is a familiar sight to shipping which pass through the Vineyard Sound;

but during long months the crew of the South Shoal Lightship see their only

connecting link between their lonely ocean home and their firesides ashore loom

up only a moment against the wintry sky, to vanish again, leaving them to their

communion with the waves and gulls, awakening longings which strong wills had

kept dormant, and intensifying the bitterness of their desolation. The day on which we steamed

out of Nantucket Harbor on the little tug Ocean Queen, bound for the

lightship, the sky was a limpid, luminous, unruffled blue, and the sea a

succession of long, lazy swells; yet before we reached our destination we

encountered one of the dangers which beset this treacherous coast. We had

dropped the lighthouse on Sankaty Head and were

eagerly scanning the horizon ahead of us, expecting to raise the lightship,

when a heavy fog-bank spread itself out directly in our course. Soon we were in

it. Standing

on until we should have run our distance, we stopped and blew our whistle. The

faint tolling of a bell answered us through the fog. Plunging into the mist in

the direction from which the welcome sound seemed to come, we steamed for about

half an hour and then, coming to a stop, whistled again. There was no answer.

Signal after signal remained without reply. Again we felt our way for a while, and again whistled. This time we heard

the bell once more, but only to lose it as before. Three times we heard it, and three

times lost it, and, as the fog was closing in thick about us, it seemed hopeless

for us to continue our search any longer at the risk of losing the opportunity

of putting back to shore before nightfall and the possible coming up of a blow.

Then, more than three hours after we had first heard the bell, it rang out to

windward clearer and stronger than before. Then there loomed out of the fog the

vague outlines of a vessel. There was a touch of the weird in this apparition.

Flying mist still veiled it, and prevented its lines from being sharply defined. It

rode over the waves far out at sea, a blotch of brownish red with bare masts;

and the tide, streaming past it out of some sluice between the shoals, made it appear as if it were scurrying

along without a rag set —

a Flying Dutchman, to add to the terrors

of reefs and rips. The weirdness of the scene was not dispelled until we were

near enough to read in bold white letters on the vessel’s side, No. 1,

Nantucket, New South Shoal. After groping around in the fog, and almost

despairing of finding the object of our search, we felt, as we steamed up to

the lightship, a wonderful sense of relief, and realized the feeling of joy

with which the sight of her must inspire the mariner who is anxiously on the

lookout for some beacon by which to shape his course. Two days later we had

what was perhaps a more practical illustration of the lightship’s usefulness.

It was a hazy morning, and the mate was scanning the horizon with his glass.

Bringing it to bear to the southward, he held it

long in that direction, while a look of

anxiety came over his face. Several of the crew joined him, and finally one of

them said, “If she keeps that course five minutes longer she’ll be on the

shoal.” Through the haze a large three-masted

schooner was discernible, heading directly for a reef to the southwest of us.

She was evidently looking for the lightship, but the haze had prevented her

from sighting us, although our sharp lookout had had his glass on her for some

time. Then too, as the mate remarked with a slightly critical smile, These captains feel so sure of their course that they always

expect to raise us straight ahead.” Suddenly there was evidence that she had

sighted us. She swung around as swiftly as if she were turning upon a pivot.

She had been lunging along in an uncertain way, but the sight of us seemed to

fill her with new life and buoyancy. Her sails filled, she dashed through the

waves with streaks of white streaming along each quarter like foam on the

flanks of a race-horse, and on she came, fairly quivering with joy from keel to

pennant. Such instances are of almost daily occurrence, and if we add to them

the occasions and they must run far up into the hundreds, if not into the

thousands — when the warning voice of the fog-bell and the guiding

gleam of the lamps have saved vessels from shipwreck, it seems as

though the sailor must look upon the South Shoal Lightship as one of the

guardian angels of the deep. Only the peculiarly

dangerous character of the coast could have warranted the Government in placing

a lightship in so exposed a position. Nantucket is a veritable ocean graveyard.

There are records of over five hundred disasters to vessels on its shores and

outlying reefs. How many ships, hidden by fog or sleet from the watchers on

shore and never heard from, have been lost on the latter, is a question to